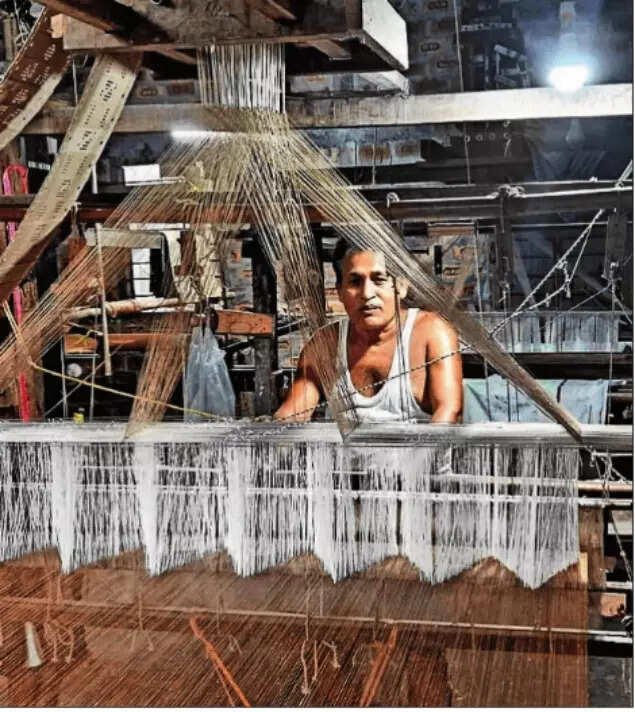

In a fast-paced world dominated by machines, the rhythmic clack-clack of wooden looms still defines the daily life of Sualkuchi. This tiny village, nestled on the banks of the Brahmaputra in Assam, is often called the “Manchester of the East.” However, unlike its industrial namesake, Sualkuchi’s heart beats for the handmade. For over a thousand years, the Sualkuchi silk weaving tradition has survived wars, economic shifts, and the threat of power looms. Today, it stands as a shining example of how cultural pride can protect an ancient craft.

Read More: Tripura Signs MoUs with Patanjali Yogpeeth Trust for ₹400 Crore Investment

A Legacy Born from Royal Patronage

The story of Sualkuchi began in the 11th century. King Dharma Pala of the Pala Dynasty established the village by bringing 26 weaver families from Barpeta. Later, the Ahom kings provided immense support to the craft. During their reign, silk was more than just fabric; it was a symbol of royalty. Only the elite were allowed to wear the prestigious Muga silk.

As time passed, the craft moved from the palace to every doorstep. Consequently, weaving became a way of life rather than just a profession. Today, it is said that “a home without a loom is beyond imagination” in Sualkuchi. This deep connection to history is the first reason why the Sualkuchi silk weaving tradition has never faded.

The Magic of the Three Indigenous Silks

Sualkuchi is famous for three specific types of silk, each with its own story:

- Muga Silk: This “Golden Silk” is exclusive to Assam. It is incredibly durable and, remarkably, its shine increases with every wash.

- Pat Silk: Known for its brilliant white color and soft texture, it is the primary choice for the traditional Mekhela Chador.

- Eri Silk: Also called “Ahimsa Silk,” it is made without killing the silkworm. It is warm, soft, and increasingly popular in sustainable fashion.

The unique nature of Muga silk, in particular, acts as a natural shield for the village. Because Muga silkworms (Antheraea assamensis) only thrive in the climate of Northeast India, Sualkuchi maintains a global monopoly. This natural exclusivity has helped the Sualkuchi silk weaving tradition remain relevant in the international market.

Resisting the Machine: The 2013 Protest

The greatest threat to Sualkuchi came not from time, but from imitation. In 2013, cheap power-loom fabrics from other states flooded the local markets, being sold as genuine Sualkuchi silk. The villagers did not stay silent. They launched a massive protest to protect their identity.

This movement led to significant changes. In 2017, Sualkuchi’s weaving earned trademark status. Now, entrepreneurs submit their products to the Sualkuchi Silk Testing Laboratory. Every piece is tested and tagged with a QR code and a 3D hologram. Therefore, customers can scan a piece of fabric to verify its authenticity and discover the artisan behind the weave. This blend of ancient craft and modern technology has helped the Sualkuchi silk weaving tradition fight back against mass-produced fakes.

A Community-Driven Economy

Unlike other textile hubs that focus on exports, Sualkuchi thrives on local demand. In Assam, wearing a handwoven Mekhela Chador is a mark of prestige during weddings and Bihu festivals. This “societal pressure” to choose handloom over power-loom provides a steady income for the thousands of people employed in the industry.

Furthermore, the craft is inclusive. In Sualkuchi, weaving is not limited by gender or caste. While it was once confined to the Tanti community, today, people from all backgrounds—including Brahmin and Koiborta families—have taken up silk weaving. This collective participation ensures that the skills are passed down to every new generation.

Why Sualkuchi Silk Endures

| Feature | Why It Matters |

| Durability | Muga silk often outlives its owner, making it a family heirloom. |

| Authenticity | QR codes and holograms shield handcrafted treasures from fakes. |

| Community | Societal pressure in Assam keeps the industry handloom-based. |

| Exclusivity | Assam holds a global monopoly on the production of golden Muga silk. |

Conclusion: The Resilience of the Golden Thread

Sualkuchi’s survival is a miracle of cultural persistence. The village has faced high raw material costs and competition from synthetic fibers. Nevertheless, the weavers have chosen to stick to their wooden looms. Their dedication proves that some things—like the golden glow of a Muga saree—simply cannot be replicated by a machine.

The Sualkuchi silk weaving tradition is more than just an industry; it is the soul of Assam. As long as there are people who value the “soul” in their clothes, the looms of Sualkuchi will continue to hum.